Presented March 5, 2024 at the Newark Public Library

.

.

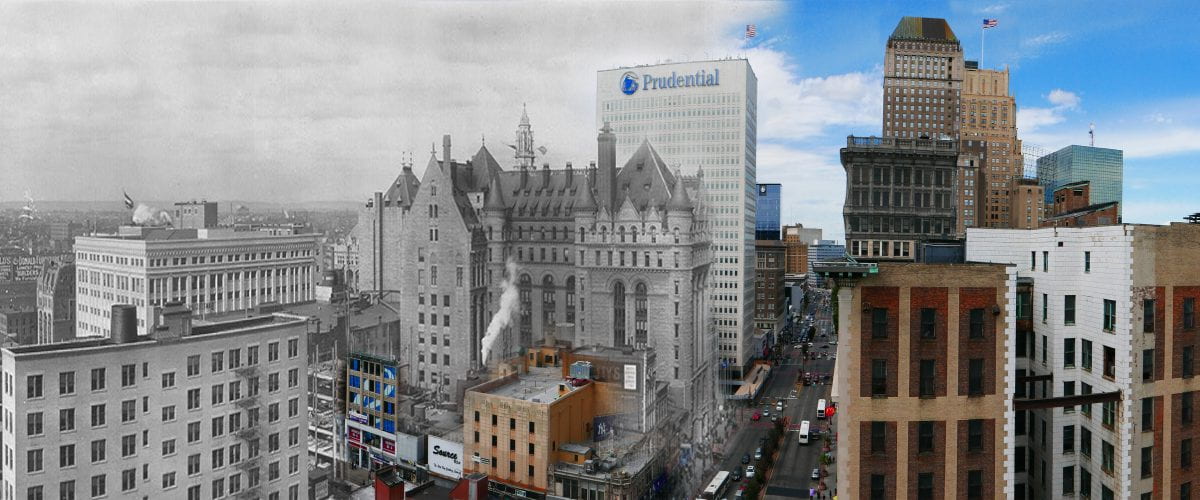

The world’s largest concentration of wealth is in the New York City metropolitan area, yet the region contains many under-resourced cities, including Newark. What historical factors created this division between low-income Newark and its wealthy neighbors along lines of race, housing, income and social class?

The agents of change are more complex and nuanced than a simple narrative of redlining and white flight following the 1967 uprising. From discriminatory actions by the Federal Housing Administration and highways that carved through the urban fabric, to suburbs that pulled middle-class families away from Newark and factories that relocated outside of the city, contemporary poverty in Newark was more than a century in the making.

Drawing from the archives of the Newark Public Library, this presentation examines the range of challenges Newark faces and how the city overcomes. This is a Newark History Society program, co-sponsored by NJPAC and the Newark Public Library. Light refreshments will be served.

The presenter is Myles Zhang, urban historian and doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

This presentation will evolve into my dissertation entitled:

“An island of poverty in a vast ocean of material prosperity”:

Homeownerhip and the Racial Wealth Gap in Newark

.

.

.

1959 Map of “Blighted” Areas by Newark Central Planning Board

.